OM System 150‑600 mm f/5‑6.3In this review:

Introduction

OM System released its M.Zuiko Digital ED 150‑600 mm f/5.0‑6.3 IS zoom (henceforth referred to as the 150‑600) on January 30, 2024. Olympus/OM System has two lines of long telephoto zoom lenses for digital system cameras. The first contains consumer and semi‑pro lenses with a lens front that extends while zooming. An early representative of this line is the Zuiko Digital 50‑200 mm f/2.8‑3.5 for the 4/3 (not Micro 4/3) system, subsequently upgraded with a faster (SWDsupersonic wave drive) AF motor. The 150‑600 is the longest focal length of any (prime or zoom) lens ever released by Olympus/OM System for the Micro 4/3 system. The original Olympus OM film SLR system did include 500, 600 and 1,000 mm prime telephoto lenses. Immediately after OM System's announcement of the 150‑600, photographers started commenting that the new lens looks suspiciously similar to the Sigma APO 150‑600 mm f/5‑6.3 DG OS Sports Numerous BBbulletin board posts accused OM System of re‑branding a Sigma 150‑600 lens, modified with a Micro 4/3 mount, with an initial price markup of around 800‑850 €. It is not unheard of for Olympus/OM System to have some of its lenses developed or produced by Sigma. According to camerawiki.org, several of the Olympus‑branded lenses for the legacy 4/3 system were modifications of Sigma lenses. The Micro 4/3 Olympus 75 mm f/1.8, 45mm f/1.2, 8mm Pro fisheye and 100‑400 mm f/5‑6.3 are likewise widely rumored to be made, or at least designed, by Sigma. Amidst the often heated discussions among BB users, a few posters pointed out that, despite the shared general appearance and overall specifications of the two lenses, there are significant differences between the OM System and Sigma 150‑600. Other posters maintained that the only differences are cosmetic, and that aside from this, the two lenses are identical, not just similar as could be expected by sharing the same FLfocal length range and lens speed. This inconsistency in opinions requires a thorough discussion. Before discussing whether the OM System lens is a rebranded Sigma lens, I should explain that Sigma currently makes three different models of 150‑600 mm f/5‑6.3 full‑frame zooms:

The Sigma APO 150‑600 mm f/5‑6.3 DG OS HSMhyper sonic motor Sports is a relatively old lens. It is longer (290 mm vs. 265 mm) and heavier (2.86 Kg vs. 2.10 Kg) than the non‑HSM Sports, with different filter mount (105 mm vs. 95 mm), and uses a different optical scheme (24 elements in 16 groups, vs. 25 elements in 15 groups for the newer non‑HSM lens). The non‑HSM model is available only in L and E mounts. The HSM model is available in Nikon, Canon, and Sigma mounts. External differences between OM System and Sigma Sports non‑HSM lensesThe immediately visible differences are:

Serial numberThe serial number of the lens is printed on a metal tag plugged into a recess of the lens barrel close to the lens mount. The serial number is also added (with two additional zeroes tacked to the end) to the EXIF data of every picture taken with this lens. Some free utilities like ExifTool can read this EXIF field (named Lens Serial Number), but many commercial software packages for image processing only display a small selection of the EXIF fields. The lens serial number is also printed on a label attached to the outside of the lens packaging. The camera's serial number is saved in the EXIF data of each picture (in the Serial Number field). A different Internal Serial Number is also stored by the OM-1, but I don't know what this value means in pictures taken with this camera. It is used for different purposes by different manufacturers, and some commercial post‑processing software overwrites the original value stored in this field. Internal differencesThe internal electronics, motors, and actuators are by necessity adapted to the Olympus/OM System and to the communication protocols between camera and lens, and this very likely improved the performance of the OM System branded lens on OM System cameras (e.g. by allowing simultaneous in‑lens and in‑camera IS), compared to the Sigma‑designed AF and IS electronics and electromechanics. Since this is an OM System‑branded lens, we should not expect the bugs that often creep into a reverse‑engineered product designed by a third‑party company that does not have access to the original specifications of the camera system. In the past, some Sigma‑branded lenses were plagued by this problem. I still remember the recurrent problem, in the 2000s, of AF Sigma lenses in Nikon F mount not working on new Nikon bodies, and having to be shipped back to Sigma for retooling (online firmware updates were not yet available). Sigma may not have been entirely at fault - it is possible that Nikon knowingly introduced firmware incompatibilities in new cameras to break the reverse‑engineered firmware of third‑party lenses. OM System states that the 150‑600 supports all computational photography functions, including in‑camera focus stacking, focus bracketing, starry‑sky AF, live ND, etc. It appears that the 150‑600 enables all advanced features of recent Olympus and OM System cameras without requiring a camera firmware upgrade specific to this lens (unless I missed such an update in the past, before I became interested in this lens). I don't know to what extent these features are supported when the 150‑600 is mounted on a camera earlier than the EM‑1 III, or on the E‑M5/E‑M10 series. At the time of writing, the lens firmware version is 1.0. On a Windows PC, correct handling of the 150-600 image stabilization requires OM Workspace software version 2.3 or later (January 1, 2024). Finally, the OM System branding implies that the 150‑600 firmware can be upgraded with the same methods used to upgrade all other Olympus/OM System lenses and bodies. The multiple practical advantages associated with the OM System branding of this lens may reassure buyers and make them more willing to pay a premium price for this lens. Optical scheme

Figure 2 and 3 are based on promotional materials that have already been published on the web by dozens of sources. The optical scheme seems to be identical in the OM System versus Sigma lens. Not only is the number of groups (15) and elements (25) the same, as well as the number of elements in each group, but the curvature and relative diameter of the optical elements are identical, as far as I can see. Some online discussions mention a slightly different number of optical elements and groups in the two lenses. In some cases, the OM System lens is compared with the wrong Sigma lens (i.e. the Sigma 150‑600 HSM, see also above). In other cases, these inconsistencies may result from a faulty interpretation of the optical scheme. For example, in the type of diagram shown in Figure 3, the air gap between two closely placed but not cemented elements (elements 8 and 9 counting from the left) may be mistaken for an additional glass element, and a single mistake of this type artificially increases by one the count of elements and decreases by one the count of groups. Other discussions state that the rear elements of the OM System lens are smaller than the Sigma. The above figures suggest otherwise. I discuss this point more in detail below. Naturally, an optical scheme published in promotional materials or catalogs is not an engineering drawing, does not contain quantitative information, and does not need to be completely faithful to the actual design. In the case of Figure 2, the optical scheme does not even show the general type of glass used for each element. In fact, it cannot be excluded that a few elements in the OM System lens are made with slightly different types of glass, with respect to the original Sigma design. Acknowledging that the optical formula has been changed with respect to the Sigma lens would be a good selling point for OM System. That they keep silent on this point suggests to me that the two lenses use exactly the same optical scheme. Even if the optical scheme and glass types are the same in both lenses, the testing method and its tolerances directly affect the image quality of the lens. The Micro 4/3 system requires a higher resolution than full frame, given the smaller absolute size of the Micro 4/3 sensels. On the other hand, a full‑frame lens needs to generate an image circle of sufficient quality twice as wide as a Micro 4/3 lens. Some lens specimens that pass a full‑frame test may be rejected in a Micro 4/3 test, and vice versa. The higher resolution standards that must be held by a Micro 4/3 lens may directly increase the cost of producing this lens. Nonetheless, it is remarkable that the two figures do show what is visually the same optical scheme. When I started collecting materials for the comparison between OM System and Sigma 150‑600, I expected to find evidence for clear under‑the‑hood differences in the optical construction. I did not. Light bafflesInternal baffles and other light‑controlling surfaces may be designed differently in lenses for different sensor formats. In particular, the "excessively large" image circle of a full‑frame lens should be restricted if the lens is used on Micro 4/3, in order to reduce the amount of stray light within the camera. This may be the function of the sleeve‑shaped baffle mounted within the Micro 4/3 lens mount (rightmost in Figure 2), which appears to be a little too narrow, compared to the diameter of the optical element located closest to the baffle. Some users have commented that the rear optical element(s) of the OM System lens seem to be narrower than in the Sigma lens. What appears narrower may not be the actual optical elements, but rather the baffle reflecting onto the surface of the rear optical element. A baffle is an effective way to restrict the image circle of the lens, without changing its optical formula. In Figure 4, the copper color is light reflecting on the large rear optical element, partly shaded by the black baffle. Another, smaller optical element further within the lens shows a greenish reflection. The rear sleeve‑shaped lens baffle must remain just wide enough to accommodate the projecting front elements of the MC‑14 and MC‑20 teleconverters. Judging from online illustrations of the Sigma 150‑600 in L and E mounts, the cylindrical rear baffle of these lenses is several mm wider than in the OM System lens (quite naturally, to avoid vignetting on a full‑frame sensor). The OM System and Sigma lenses may also differ in their internal baffles, which may be very difficult to detect without disassembling both lenses. The plastic baffle at the rear of the lens is also interesting because it is marked as "Made in Japan" (Figure 5). The significance of this is discussed below. The large majority of OM System lenses are marked as "Made in Vietnam". A clone or not a clone?My conclusion about the similarities between the OM System and Sigma lenses is that OM System did commission Sigma to produce a slightly modified version of its 150‑600 mm Sports lens, branded OM System. Likely, the modifications include a stricter test of these lenses, since the smaller sensor size requires a higher IQimage quality. New electronics, and perhaps electromechanics, were also developed. These hardware changes, together with changes in the testing procedure, may partly justify the increase in lens price, compared with the original Sigma lens. The latter has been in production for about three years, which has allowed its original price to drop. The OM System lens probably would have been much more expensive if designed from the ground up, thus requiring a new assembly line altogether. The OM System 150‑600 can very likely share almost entirely the existing Sigma 150‑600 assembly line. The OM System 150‑400 TC Pro, designed from the ground up by (or for) OM System, costs roughly two‑and‑a‑half times the price of the 150‑600. Perhaps the final price of the 150‑400 TC Pro, out of the reach of most amateur photographers, is one of the factors that spurred OM System to seek the collaboration with Sigma in the design and production of the 150‑600. The latter is far from being a cheap lens, but definitely more affordable. Sigma has no published plans to introduce a Micro 4/3 version of their 150‑600 Sports lens. One reason is that they abandoned the Micro 4/3 format over one decade ago. Another likely reason has nothing to do with lens technology. When Sigma and OM System entered the agreement to jointly develop and produce the OM System 150‑600, almost certainly this agreement precluded Sigma from releasing its own, Sigma‑branded version of this lens in Micro 4/3 mount. Therefore, I believe it would be useless to wait for a Sigma Micro 4/3 version of this lens, cheaper than the OM System version. Lens coatingsAccording to a few reviews, as well as OM System, the OM System lens, like many others, has what they call "fluorine" coatings to prevent the adhesion of water and oily substances. What is fluorine? Fluorine (chemical symbol F) is the element with atomic number 9. It is a non‑metal, and in particular it is a halogen. It is a gas at ambient temperature and pressure (and remains a gas also at very low temperatures). Therefore, it is impossible to use fluorine to coat a lens and make it stick onto the lens for longer than a second or two. Tripod collar and shoeThe tripod collar seems to be identical in the OM System and Sigma lenses. This collar, with two integral eyelets for a neck strap, is quite similar in construction to the collar of the white OM System 150‑400 TC Pro. Note that prototypes of the OM System 150‑400 TC Pro (e.g. see 43rumors and bomsellmk) show two strap eyelets made of stainless steel and bolted onto the metal alloy of the collar. However, this feature was dropped in favor of eyelets integral with the collar and placed differently in commercial specimens of this lens. The position of the collar locking knob also changed as a result of this redesign. The collar shoe of the 150‑600 is equipped with an Arca‑compatible shoe, like the other current Olympus and OM System long lenses, as well as several (albeit not all) current Sigma long lenses. The bottom of this shoe has two threaded sockets for M3 bolts, which prevent the shoe from sliding out the front or rear of a not completely tightened Arca‑compatible clamp. My specimen of the lens came without these safety bolts (both the OM System 150-400 TC Pro and the Sigma 150-600 Sports are likewise delivered without these safety bolts). All my earlier Olympus/OM System lenses equipped with Arca‑compatible shoe came complete with safety bolts. The main reason for removing the safety bolts is when the lens needs to be attached to a tripod head via the 1/4"‑20 treaded socket at the bottom of the shoe. The bolts make no difference to the hand‑holding of the lens, but prevent the bottom of the shoe to sit steady against a flat surface. At least in Europe, it is easy to find in hardware stores the right type of stainless steel bolts with Allen heads for the shoe. The missing strap eyelets on earlier lenses, including the 300 mm f/4 Pro, are in my opinion a significant omission. They force me to attach a neck strap to the 1/4"‑20 socket of the tripod shoe, preventing a quick switching between hand‑holding and tripod mounting. The lack of a removable tripod shoe is a further omission in these lenses. The lens collar can be rotated freely after releasing its locking knob. There are no detents at the angles indicated with white dots on the lens barrel. The lens collar cannot be removed from the lens barrel. AccessoriesA flat, broad (40 mm for most of its length) neck strap of synthetic ribbon accompanies the lens, and can be mounted on the eyelets of the lens collar. The strap is not padded, except for a thin layer of non-slip rubbery material on one side. Unlike Olympus and OM System camera straps, it carries no branding whatsoever.

The Sigma 150‑600 can be equipped with the LC‑747E padded "sock" (Figure 6) that covers the front of the reversed lens shade, fastens around the locking knob, and may help to protect the lens shade and the front of the lens during transportation. The sock can be placed also on the forward‑facing lens shade, but in this orientation it will stay in place only by friction. This sock is available for separate purchase, but is rather difficult to find and out‑of‑stock at most Sigma representatives. It contains a stiff disk sewn into the front of the sock, which prevents contact between the sock and front element of the lens even if the front lens cap is missing. The interior of the sock is lined with a soft, non‑abrasive cloth. At present I carry the OM-1 with OM System 150-600 and its lens shade forward mounted in a Tenba Solstice 10 l swing pack, resting with the lens shade at the bottom of the pack. During transportation to and from the field, and during storage in the pack at home, the lens usually carries both its plastic front cap and the Sigma sock. When switching locations on foot in the field, I usually put back on only the sock, so that it takes just a few seconds to swing the pack to my chest, pull the camera out, pull out the sock, and turn on the camera. The front element of the lens sits at the bottom of the "well" of the lens shade, several cm away from the bottom of the sock. The sock is made in P.R.China, and is therefore an exception to the general rule that Sigma manufactures all its equipment in Japan. It is otherwise not visibly branded. My OM System 150‑600 did not come with a sock, but I purchased the Sigma sock in the above figure on eBay. It fits perfectly on the OM System 150‑600. Note that the sock for the Sigma 150‑600 HSM Sports is wider, and does not fit the OM System 150‑600 or the Sigma 150‑600 non‑HSM Sports. The OM System 150‑400 TC Pro does come with a sock of this type, of course larger than the one for the 150‑600, but so close in appearance that it almost certainly comes from the same factory (it is, however, branded Olympus on its front). OM System‑branded front and rear caps come with the OM System 150‑600. Both are made in Vietnam, so they come from OM System factories, not Sigma. IS, AF and close focusThe OM System 150‑600 provides combined in‑body and in‑lens IS with high‑end Olympus/OM System cameras. OM System calls this capability Sync IS. There is a Lens IS Priority setting in the OM-1 menu, but it has no effect with lenses that allow Sync IS. In other words, with these lenses, you cannot choose whether to use only in-lens or only in-camera IS. Both types of IS are either on simultaneously, or off simultaneously. The lens uses stepper motors to move the internal optical groups when focusing. In the past, stepper motors were generally regarded as slower and noisier than the linear servos used in most modern lenses. However, stepper motors have an edge over linear servos when moving heavy optical groups over relatively long distances. The OM System 90 mm macro, for example, uses a stepper motor for internal focusing, for the very same reason. Tamron uses a stepper motor in its (so far) only Micro 4/3 lens, so OM System is not alone. The focus ring performs focus‑by‑wire, i.e. not mechanically but electronically. The minimum focusing distance changes with focal length. The following data are reported by OM System:

In order to reach the highest magnification, it is therefore necessary to zoom out to 150 mm FL. Sigma specifies a slightly different close‑focus distance for its 150‑600 Sports, namely 0.58 m and 2.8 m, respectively. According to my tests, the OM System data are the distance between subject focus plane and sensor plane. In close‑up and macro photography, however, it is more useful to specify the working distance, i.e. the minimum distance between the front of the filter mount of the lens and the subject. In my tests, the working distance is:

The lens aperture can stop down to f/22 at all FLs. Physical measurementsThe diameter of the filter mount is 95 mm. The lens length when completely collapsed is 264.4.mm, with a diameter of 109.4 mm (excluding the lens shade, tripod collar and shoe). At maximum extension, the lens length is 365.8 mm, or 432 mm with the lens shade mounted in forward orientation. As a comparison, the 300 mm f/4 Pro is 224 mm long (with lens shade retracted) and 92.5 mm in diameter. Lens weight is 2.07 Kg without caps and lens shade. The LH‑103 lens shade, with a diameter of 120 mm (excluding the locking knob) and a length of 84.6 mm, adds another 151 g, and should always be used when shooting outdoors. The lens shade can be mounted in reversed orientation, and is locked by twisting a rather large and projecting knob. Weather sealingThe 150‑600 is equipped with a complex system of weatherproof seals. The extending front of the lens is a weak point in the weather sealing because the zooming movement causes a large amount of air to be pumped into and out of the lens barrel, unavoidably carrying both humidity and dust into the lens. The weather sealing of the 150‑600 is IPX1 certified. The IPX1 test procedure is an exposure for 10 minutes to vertically falling rain equivalent to 1 mm water per minute on the lens in horizontal orientation. Note that neither zooming nor refocusing while exposed to rain are allowed during the IPX1 test. Some of the other Olympus/OM System lenses and cameras are certified up to IP53 (water sprays up to 60°, and additionally protected against dust penetration in amounts that can interfere with the functioning of the device). This includes e.g. the 40‑150 mm f/4 Pro and 300 mm f/4 Pro, as well as the MC‑14 and MC‑20 TCs. Whenever equipment with different IP/IPX certifications is assembled together, only the lowest certification (in this case IPX1) applies to the assembled equipment. Neither IPX1 not IP53 guarantee protection against immersion in water. Fine dust like color powders (thrown in the air in some Indian festivals and western "Color Runs" and "Fun Runs"), as well as salt spray on beaches and near sea water, are also known to penetrate the weather seals of camera lenses and contaminate the lens interior, requiring costly repairs or the purchase of a new lens. Salt spray is also corrosive and may ruin electronic and mechanic components. ZoomingZooming in (i.e. toward higher FLs) requires the zoom ring to be turned counter‑clockwise (as seen from the rear). This is the same direction as in my other Olympus and OM System zooms. It is also the same as in the Sigma 150‑600. The focal length recorded in the EXIF data of images corresponds well with the markings on the zoom ring, except for the 400 mm marking, which is consistently recorded as a little shorter in EXIF (usually 391 mm). The internal focus design of this lens implies that the actual FL decreases at closer focus distances, with respect to the nominal FL.

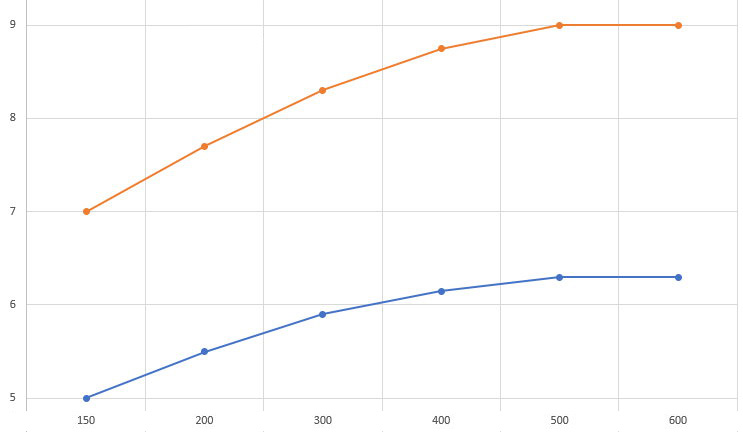

Blue line: without TC. Orange line: with MC‑14. Recorded f/ aperture on vertical axis, nominal FL on horizontal axis. Figure 7 shows the change in lens speed (as reported in the image EXIF) while zooming. All test images were shot with the aperture fully open. The blue line in the diagram shows the lens without a TC, the orange line with MC‑14 (1.4x TC). There is apparently no decrease in lens speed between 500 and 600 mm FL. The change in lens speed is fastest at the low end of the range of FLs. Therefore, if you want/need as much lens speed as possible (e.g. to reduce the risk of motion blur of the subject), and you are at 400 mm FL or lower, consider zooming out by a moderate amount. For example, by zooming out from 200 to 150 mm FL, you gain almost half a stop, which is a modest amount but may make a difference. Between 400 and 600 mm FL, it makes little practical difference. Fast zooming the 150‑600 is possible by pushing and pulling the front of the lens. This is best done with the palm of the left hand placed under the lens, with the thumb and index fingers extended to grab the circumference of a rounded black ring at the point where the cylindrical extending barrel begins to flare out in a broad cone. While unorthodox, this method of zooming is explained in the user guide and the rounded ring is provided for this use. Therefore, unless done with extreme energy, this way of zooming should not involve a risk of damaging the lens mechanisms. This works best when the zoom friction slider is set to S (smooth). It does succeed with the slider set to T (tight), but should not be attempted with the slider set to L (locked). Virtually the same instructions for fast zooming are also found in the user guide of the Sigma 150‑600. In the past, I had the habit of using a "gravity assist" when zooming the legacy Sigma 50‑500 mm, which also has a large and heavy extending lens front. This technique consists in pointing the lens up or down when zooming out or in, respectively, by turning the zoom ring. The weight of the lens front helped its sliding movement. This technique is also applicable to the 150‑600, although the push‑pull technique is faster. The OM System lens seems to remain parfocal when zooming. I cannot exclude that AF may need to perform a slight focus adjustment when zooming all the way across the FL range, but certainly no major adjustment. When half‑pressing the shutter button in C‑AFcontinuous AF or C‑AF+MFcontinuous AF with MF override modes, the AF always "hunts" for a fraction of a second, especially in low light. This may mean that the camera has switched from phase AF to contrast AF in these circumstances, but the refocusing is too brief to be a problem. Pro versus non‑Pro lensesThe 150‑600 is not marketed as a Pro lens. A comparison with other lenses shows apparent inconsistencies between Pro and non‑Pro lens denominations. For example:

According to some sources, Pro lenses are supposedly made mostly of metal, while non‑Pro lenses are made to a larger extent with plastic structural parts (excluding of course the optical elements and electronics). Many modern lenses have external and internal barrel sections made of metal, but they tend to be relatively thin and lightweight metal sleeves, not heavy parts as frequently seen in camera lenses manufactured until approximately the mid 20th century. Several internal parts of the Sigma 150‑600 are made of metal, for example. Structural plastic is often used for complex shapes that would be difficult and expensive to cast or machine in metal. As a whole, the statements that Olympus/OM System Pro lenses are assembled mostly or exclusively from metal parts should be taken with a generous grain of salt. Camera lenses made entirely of plastic (except for the optics but sometimes including structural parts like the lens bayonet) were briefly popular in the late 20th century to the first years of the 21st century. Even some early Micro 4/3 lenses were made almost entirely of plastic. At present, Micro 4/3 lenses tend to be of higher quality, and to contain a mix of metal and plastic parts, while lenses made preponderantly of metal prevail among China‑produced third‑party lenses devoid of electronics and electromechanics. Structural parts correctly designed and made from high‑quality composite plastics reinforced with carbon or glass fibers are both strong and precise without being excessively heavy, more resilient, and more likely than metal parts to survive accidental impacts without permanent deformation. However, some structural parts, and especially the lens bayonet, are way too fragile if made from composite plastics, since these parts were originally designed to be made from metal. It was common for lenses equipped with plastic bayonets to prematurely end in a dust bin because the bayonet literally broke off the lens and part of it remained lodged in the camera. Image quality has also been mentioned as one of the things that separate Pro and non‑Pro lenses. All the Pro lenses in my possession give an excellent image quality. I have less direct experience with non‑Pro lenses, but the 12 mm f/2 non‑Pro in my possession is at least as good as the 12‑40 mm f/2.8 Pro in terms of IQ. The 75 mm f/1.8 non‑Pro is generally recognized as one of the sharpest Olympus lenses. The 60 mm f/2.8 macro non‑Pro is likewise regarded as very good. On the other hand, in the early Micro 4/3 years Olympus released a few consumer‑level lenses of unremarkable quality. Among these, I only owned the 17 mm f/2.8, and found it unsatisfactory both optically and mechanically. In conclusion, it is not completely clear to me which criteria Olympus/OM System uses to market certain lenses as Pro, and others as consumer‑level. One of the reasons is that Olympus/OM System lack an "official" category for semi‑pro lenses, so their consumer‑level (a.k.a. non-Pro) category is a mixed bag of lenses of varying quality. Their Pro lenses, on the other hand, are more consistent in characteristics and performance. Physical controlsThe lens is equipped with a large zoom ring near the front of the fixed portion of the barrel, and a thinner focus ring to the rear of the zoom ring. The 150‑600 focus ring does not have the AF/MF clutch typically found on Pro lenses. The OM System 150‑400 TC Pro likewise has an AF/MF slider instead of a focus clutch. It would probably be difficult to operate a focus clutch on a focus ring this large in diameter but narrow in length. Between the two rings are:

Replacing the AF/MF clutch with a slider switch changes the handling of this lens, compared to most of the Olympus/OM System Pro lenses. More than once, I accidentally switched a Pro lens from AF to MF while handling or hand‑holding the lens in the field, and missed an opportunity when AF did not work. It may take a few seconds to remember to check the AF/MF clutch, especially if you did not intentionally operate it. It is far less likely to accidentally operate the AF/MF slider of the 150‑600. The AF/MF clutch, when present, can be disabled in the settings menu, and this, coupled with configuring the focus ring to switch to MF when turned (with the AF+MF setting), can replace the function of the AF/MF clutch. Also this alternative, however, may cause the photographer to miss a shot if the focus ring is inadvertently turned while handling the lens, unexpectedly disabling AF. In the OM System 150‑600, however, the focus ring is normally out of the reach of the left hand, so this should not be a problem. Replacement tripod shoeUnavoidably, the position of the center of gravity of the 150‑600 shifts toward the front of the lens when the latter extends. For this reason, some users leave a 10‑15 cm long Arca‑compatible plate permanently attached to the tripod shoe of the lens. Without this added plate, the lens is substantially front‑heavy when extended and mounted on a tripod or monopod by its built‑in tripod shoe. A longer tripod shoe also makes a better handle to carry the lens in the field. Some photographers turn the lens collar of long telephoto lenses upside down and carry the lens with attached camera by this handle. It is also possible to attach accessories to the upturned lens collar, e.g. an electronic flash, flash controller, or red‑dot viewfinder. The tripod shoe that comes with the lens is not safe to use as a carry handle for the lens. It is far too short for this use.

The user guide of the OM System lens says "The tripod mount and tripod mount foot cannot be removed." This actually means that the shoe is not designed to be removed and reattached in the field, since doing so requires an Allen key to turn the four M4 machine screws holding the shoe attached to the collar, as well as care not to lose the screws. The screws have been tightened at the factory, but not secured with thread sealant. It may take some effort to loosen them the first time. The user guide of the Sigma 150‑600 does show how removing the shoe displays a 1/4"‑20 threaded socket on the base of the collar. Following these instructions reveals a nice 1/4"‑20 threaded socket in a steel insert also in the OM System 150‑600 (Figure 9). The web page for the Sigma 150‑600 explains that the TS‑121 tripod shoe that comes with the lens can be replaced with the much longer and massively overpriced TS‑81 shoe available for separate purchase. The TS‑101 shoe is intermediate in length and price between the two above models. It is specified for the Sigma 60‑600 lens, but seems to be compatible also with the 150-600. Apparently, multiple Sigma lens models use the same attachment for the tripod shoe. Replacing the default tripod shoe of the OM System 150‑600 would seem a more compact alternative than fastening a long Arca‑compatible plate under the default lens shoe. At least three different models of third‑party tripod shoes, branded iShoot, Haoge and Leofoto, are advertised at present on Amazon EU at prices far lower than the Sigma shoes. These tripod shoes seem to be compatible with the OM System 150‑600. The compatibility list of the iShoot tripod shoe reads:

The Haoge replacement shoe (Figure 10) is significantly longer than the original shoe of the OM System 150‑600, apparently strong, and reasonably well made without being excessively heavy. Its design with a T‑shaped (in cross‑section) joint between foot and collar is reminiscent of the OM System 150‑400 TC Pro. It allows a five‑fingered grip to securely hold the lens, and slightly increases the distance between the shoe and the lens barrel with respect to the original shoe. It allows with ample margin the lens shade to be reversed onto the lens for storage. This shoe does not have an attachment for a neck strap. Some third‑party tripod gimbal heads are limited in the distance they allow between foot and center of mass of the lens. In this case, a Sigma replacement foot, or a long Arca-compatible plate directly attached to the lens collar after removing the original shoe, might be a better choice than the Haoge shoe. When hand‑holding, the lens can be supported with the original shoe resting on the palm of the left hand. With the Haoge shoe, unless you have unusually long fingers, you may not reach the zoom ring. As an alternative, you may rotate the the tripod collar and shoe out of the way, and place your left hand directly under the zoom ring. The Haoge shoe may require a little more space to store the lens in a camera backpack. The bottom of the shoe carries three 1/4"‑20 threaded sockets (directly machined in the aluminum alloy of the shoe) and two M3 Allen screws that prevent the shoe from accidentally sliding out of a clamp, and is 89 mm long. With the Haoge shoe and no camera attached, the lens rests on a flat surface with the lens shade mounted in forward position without tipping forward, but only until the lens is zoomed to about 250 mm FL. With an OM‑1 attached, the lens can be zoomed fully to 600 mm FL without tipping forward. Some of the other third‑party replacement shoes for the Sigma/OM System 150‑600 have been criticized by buyers for their screw holes too tight for the screws, and/or slightly misaligned with the threaded sockets on the lens collar. This is not the case with the Haoge shoe. The screws accompanying some replacement third‑party foot have been reported to be too short. The machine screws that came with the Haoge shoe are shorter than the original ones (10 vs. 15 mm). However, the original OM System screws are too long for this shoe, so I used the Haoge screws instead. The iShoot lens shoe has machined grooves on the sides of the shoe that do not extend to the rear end of the shoe, and therefore cannot be fully pushed forward into a clamp. I dislike this type of poorly planned design "accident". Lens shadeThe thin plastic lens shade has a rubber‑coated front edge and feels quite lightweight. The locking knob of the lens shade presses a plastic tab into a shallow groove around the front of the lens barrel. This mechanism appears identical to the one used on the 150‑400 TC Pro. After loosening the knob, you must continue to turn it for over two full turns, in order to free the tab from the lens groove. This is a safety mechanism that prevents the lens shade from falling off if the knob accidentally loosens in the field. Do not force the lens shade off the lens unless you have fully unscrewed the locking knob. Also, do not overtighten the locking knob. The locking mechanism, and the lens shade as a whole, do not seem to be very strong, and easily flex. An important property of lens shades is that, with a given lens, a camera with a smaller sensor can use a narrower lens shade without causing vignetting. A narrower lens shade provides better protection against e.g. direct sunlight hitting the front lens element. The lens shade of the Micro 4/3 OM System 150‑600, however, does not seem to have been modified according to this principle, compared to the full‑frame Sigma 150‑600. The probable reason is that the internal diameter of the lens shade cannot be substantially reduced while still allowing the lens shade to be reversed onto the front of the lens. Instead of decreasing the diameter of the lens shade to fit a smaller sensor (or adding a circular baffle at the front of the lens shade, which achieves the same optical result), the alternative is increasing the length of the lens shade. This protects even better against stray light, as long as it does not vignette at the lowest FL. Some professional‑grade extreme telephoto lenses are equipped with a two‑stage lens shade. The second stage can be added at the front of the first stage in particularly demanding illumination conditions. The two stages can sometimes be nested within each other for storage. An improvised extension for the lens shade of the OM System lens could be made from a sheet of matte black cardboard rolled around the lens shade and held closed by gaffer tape or a rubber band. It would likely need to be removed when using the lens at its lowest FLs. TeleconverterThe 150‑600 can use either the MC‑14 or MC‑20 teleconverters. The results with MC‑14 are good on distant subjects if the lens is stopped down no more than half a stop, but in practical use I hesitate to mount a TC on the 150‑600. The lens without TC at 600 mm FL is already difficult enough to shoot with handheld. In any case, it makes no sense to use a TC‑14 for shooting at nominal FLs of 425 mm or less (600 mm effective FL, or less). In theory, in wildlife photography there is no such thing as "too much FL", but in practice one quickly hits the point of diminishing returns in terms of sensitivity to camera and lens vibration, atmospheric turbulence, and lens diffraction. Tests of the 150‑600 with the MC‑20 TC are mainly of theoretical interest to me, because I regard this combination as beyond the realm of feasible use, even with a heavy tripod and gimbal head and shooting with fully electronic shutter. With the MC‑20 and zoomed to nominal 600 mm, the effective aperture becomes f/16 if closed by about half a stop. Unavoidably, diffraction blur is quite visible. While the 300 mm f/4 Pro does produce acceptable results with the MC‑20, and becomes an effective 600 mm f/8, the 150‑600 at 600 mm begins to show its limits already with the MC‑14. This is caused by a combination of high FL, slower effective aperture, incipient diffraction blur, and lower intrinsic lens resolution. By all means, feel free to try this lens with the MC‑20 if you do have the equipment and can shoot from an elevated position, preferably short after sunrise in the hot season, but do not expect miracles. Nonetheless, in optimal conditions your results should be at least usable, especially with subjects not farther away than 30‑40 m. It is feasible to use the MC‑14 to enhance the close‑focusing capabilities of the 150‑600 at nominal 150 mm, e.g. for closely‑cropped portraits of extremely skittish or poisonous small subjects at up to 0.49x and close to f/10 (effective) fully open. This is slightly affected by diffraction blur, but still acceptable for some uses. With the MC‑20 at nominal 150 mm FL and focused at 0.7x, effective aperture becomes approximately f/15 fully open, which is firmly in diffraction territory. Place of manufactureSigma evidently takes pride in doing all their lens production in their factory in Aizu, in the western part of Fukushima Prefecture, Tōhoku Region, Japan, for slightly more than 50 years. This includes lens grinding, optical assembly and testing, as well as machining of screws and other metal and plastic parts. The 1,400 Sigma employees at this factory produce around 1,000,000 lenses a year. While Sigma is known among photographers as a maker of third‑party lenses, as well as a line of system digital cameras that use a sensor of unusual design, the company also manufactures plenty of OEM camera lenses that are branded with other famous brands. Olympus and OM System have a tradition of designing photographic equipment in Japan and producing it largely in lower‑cost Asian countries. In the past, these countries included China, but the factories were moved to Vietnam in recent years. The OM System 150‑600 is therefore one of a minority of OM System lenses produced in Japan. Other examples include the Olympus 100‑400 mm. Lens handling techniqueAs always with a long telephoto lens, you must be careful when attaching a camera to the lens. Note that the preceding sentence is correct: in this case you must attach the camera to the lens, not vice versa. Securely hold the lens with its rear uppermost (or place the lens with its front down on a flat surface), remove its rear cap and the camera cap, then carefully mount the camera body onto the lens, and twist the camera body (not the lens) clockwise until it clicks in place. Never lift or carry the assembled lens + camera by holding the camera. Never hang the assembled lens + camera by the camera strap. Always hold it by the lens, and hang it by the lens strap. If you are using a camera strap that can be quickly detached, like the Op/Tech strap system, it is a good idea to take it off after attaching the camera to the 150‑600. This way, you only have one neck strap to handle. Finding the intended subject by panning the lens at the higher focal lengths is quite difficult, even for experienced users. There are workarounds, including e.g.:

Additionally, a posture comparable to the one used by standing rifle shooters can help to steady a super‑telephoto lens. While facing toward the subject:

A monopod or tripod is often obligatory after a few minutes of hand‑holding, as the extreme focal length "amplifies" the physiological muscle tremor and involuntary movements of the photographer, making it difficult to hand‑hold the subject framed as planned by the photographer. IS may introduce a "lag" in camera movement that can result in overshooting the subject when panning. Stopping down to f/8 or f/11 to increase the DOF already hits the diffraction limit of Micro 4/3, and forces a higher ISO with consequent noise, and/or an exposure time long enough to cause images blurred by movement of the subject (even a rock‑steady tripod cannot prevent the subject from moving). My initial testsI decided to carry out a few simple tests just to verify that my specimen of the 150‑600 works as expected. With the 300 mm f/4 Pro and, most of the time, MC‑14, I shoot generic subjects in A mode with C‑AF+MF, and wildlife (almost always birds) in A mode with Subject Recognition, Bird C‑AF+MF. Therefore, this was a good way to start testing the 150‑600. All test images were shot at 400 ISO, stored as superfine JPGs, and the figures show the test images straight out of the camera, reduced or cropped as necessary, and saved as 75% JPG quality in order to reduce file sizes for the web, but otherwise not post‑processed. Indeed, image compression for web publication does cause a small but visible deterioration of IQ, especially in 1:1 pixel crops. A Mode, C‑AF+MFI carried out this test with a moored tugboat over 100 m away as a subject, shooting mostly across open water, at 150, 300 and 600 mm FL at ISO 200, f/11 and 1/500 s in full sunlight. The results are as expected. The 300 mm would probably produce a slightly better resolution at 300 mm FL, as well as 420 mm with MC‑14, when looking at 1:1 pixel crops, but the results with the 150‑600 are fully acceptable to me. The finest detail is on the order of 1‑2 pixels across (e.g. the fine network of cracks in the white paint near bottom center of Figure 13. Shooting at f/8 instead of f/11 would give a slightly improved resolution in the 1:1 pixel crops. A Mode with Subject Recognition, Bird C‑AF+MFFor this test I went to a pair of great crested grebes (Podiceps cristatus) nesting a short walk from my place. I used the same settings, described here, that give me good results with the 300 mm f/4. This time, however, the results are obviously not as good as I expected, especially at 600 mm FL. Subject recognition correctly identified the bird's eye, but the image is blurred when displayed at 1:1 pixel ratio. For the new test of Figures 21-22, I set manually a value of 400 ISO and used the electromechanical shutter. The results are visibly better. The 150‑600 is quite sharp between 150 and 400 mm at f/5‑f/6.3, but less so at 500‑600 mm FL. So far, at 600 mm my best results are with the lens stopped down to f/8 or f/9.5 (Figure 23‑24). This increases the lens sharpness and seems to correct (thanks to the higher DOF) small AF errors. As a whole, the increased DOF also produces better pictorial results because of the much "creamier" bokeh behind the subject (although naturally it does reduce the "separation" between subject and a nearby background). These two figures were obtained with the same Auto ISO and other settings I normally use with the 300 mm f/4, so in my case it seems the simplest solution is to stop down the lens. Some users complain that the 150‑600 is not sharp (see also next section). I agree that this lens is not as sharp as the 300 mm f/4 Pro. It is, however, reasonably sharp. My tests suggest that, at least in some if not all of these negative experiences, the problem is likely not with the optical sharpness of the lens, but with lens handling technique and/or with the choice of camera and lens settings. A problem with stopping down is that Auto ISO, in overcast weather, forces a high ISO that significantly reduces image contrast and resolution (at all apertures from f/6.3 to f/9.5). This is evident at high latitudes, where direct summer sunlight is 1‑2 stops weaker than in southern Europe, further decreases by 2 more stops in winter, and an overcast sky may reduce the available light by yet another 2‑4 stops.

At this light level, shooting with the 300 mm Pro at f/4 may produce better results, in spite of the need for extensive cropping in post‑production. I live in central Sweden, at the same latitude as southernmost Greenland and Homer, Alaska, so low levels of daylight are a common problem. Hopefully, in the near future OM System and/or professional users of the 150‑600 will provide more information on the optimal camera settings for this lens. OM System might be able to release an updated lens or camera firmware that will allow Subject Recognition and/or AF to work better with the 150‑600 at the high end of FLs. In the mean time, scouring the Internet did reveal that a minority of the OM‑1 users did/do have problems with AF, especially with an early batch of these cameras. A number of potentially incompatible combinations of camera settings that make things worse have been discussed. I don't know for sure what is the cause and whether the proposed solutions work, but I am just listing some of them. Also, some of these problems may have been solved with firmware updates of the OM‑1. The following list contains known and suspected problematic settings, as well as settings that may help the use of the 150‑600.

Note that there is also a different setting to control release priority, accessible through Menu → AF → 1.AF → Release Priority. This setting is not connected to the firmware AF Limiter, and is not the setting discussed above. Chromatic aberrationBefore post‑processing, showing transversal chromatic aberration.

Micro 4/3 lenses are supposed to communicate to the camera the parameters required to correct multiple types of lens aberrations in‑camera, mainly transversal chromatic aberration and geometric distortion. However, some of my test images shot at 600 mm FL in conditions of strong backlighting and/or bright backgrounds do show visible amounts of transversal chromatic aberration (blue and orange edges of the black parts of the subject in Figure 25‑26, top). These images respond well to post‑processing to remove this aberration. For post‑processing I used Picture Window 8, which is free for personal use, to manually correct this aberration. It is likely that, in normal conditions of contrast, the camera applies the proper amount of CA correction. I did not notice CA in subjects of normal contrast. User feedback (and its problems)Some of the feedback from buyers of the 150‑600 left on online shops like Amazon is starkly negative. In evaluating this negative feedback, one should keep in mind that some of the buyers of this lens probably have little or no previous experience with a long telephoto lens (particularly because this is the longest FL ever available in the Micro 4/3 system). A 600 mm on Micro 4/3 is equivalent in field of view to a 1,200 mm on full frame. Without proper lens‑handling technique, this focal length will almost invariably produce disappointing results. In most full‑frame systems, the maximum FL is often 800 or 1,000 mm, and impossible to hand‑hold. The image of a medium‑sized bird shot with a super‑telephoto lens generally displays an extremely low DOFdepth of field, in extreme cases with just one eye of the subject fully in focus. The foreground and background, even in proximity of the subject, show an evident OOFout of focus blurring. Visually, this type of image often "lacks depth", in the sense that objects located at the rear of the subject are not reproduced at detectably smaller sizes, causing an artificial‑looking "compression" of the depth cues. This is sometimes described as the subjects looking like flat papercuts, rather than three‑dimensional. These characteristics may come as a surprise to photographers with little experience of extreme telephoto lenses, but they are hardly a fault specific to the OM System 150‑600. Many users are also not expecting the air between camera and subject to blur an image by convection, when shooting distant subjects along a line‑of‑sight close to sunlit land or warm water. Figure 27 A shows a distant landscape, several km away, at 150 mm FL. The closest trees look fine, while the most distant shore, at the center, is affected by haze and fog (note the rolling bank of fog and low clouds along the horizon). Figure 27 B shows the farthest shore at 600 mm FL. Even at this reduced size, one begins to notice that the trees, especially on the right side of the image, look somewhat "fuzzy". Additionally, the trees closest to the center of the frame on either side of the open water seem to be floating in the air. This is a common form of mirage. Even though the air was still and cold in this case, the use of an extreme telephoto lens reveals that mirages can occur in almost any condition, if one looks far enough with a long enough FL. The unaided eyes, in these conditions, only perceive a faint "shimmering" close to the horizon, which can easily be mistaken for sunlit reflections on the water. Figure 27 C shows a 1:1 pixel crop of this portion of the image. Note that the image is fuzzy in a peculiar way, more like a painting with individual dabs of different colors clearly visible, than like an ordinary fuzzy/unfocused picture should look. This is the typical look of the optical fuzziness caused by air turbulence, and no extreme telephoto lens can do anything about it. If you use a short exposure time, the "mottling" becomes stronger. If you use a longer exposure time, the shimmering becomes averaged in time and the mottling is less evident, but the image becomes fuzzier. Correcting a limited amount of air turbulence is done, at astronomical observatories, using laser beams to measure the turbulence in real-time, and adaptive optics that can correct this turbulence in real-time. Large-aperture telescopes without adaptive optics and fast extreme telephoto lenses with large front elements can actually produce worse results than shown in Figure 27 C. result in a "veiled", low‑contrast image. Leaves and sticks protruding along the line of sight are so much blurred by defocus that they turn into a veiling glare covering the whole frame (Figure 28). This may be confused with low lens contrast, or lens flare. Atmospheric haze may also lower contrast, sometimes at distances of just 20‑30 m. These factors, and a few more not discussed here, may explain a part of the negative user feedback for this lens. As discussed in the preceding section, the camera settings seem to affect IQ with this lens. At least some of the negative experiences with this lens reported by users may, at least in part, be caused by combinations of camera settings unsuitable for this lens. Finally, some of the negative feedback may be caused by an occasional defective or underperforming specimen of this lens. In past decades, Sigma was known for the inconsistent performance of individual lens specimens. In recent years, Sigma has been trying hard to correct the traditional customer perception of this brand as a mass‑producer of relatively cheap lenses of inconsistent quality, and in 2021 stated that they measure the MTFmodulation transfer function of each individual Contemporary, Art, and Sports lens before it leaves the factory. However, they do not supply these MTF measurements with each lens, although in principle they could do so at a very limited additional cost (a one-page printout packaged with the lens would suffice), for the sake of transparency toward customers. They do not specify the pass/fail tolerances used in their MTF tests, either. Without this information, it is impossible to judge the practical impact of these tests in preventing out-of-specification lenses from being released onto the market. Branding the lens with an OM System logo causes buyers to expect a higher consistency than customary for Sigma‑branded lenses, and stricter testing should be expected to cause a larger percentage of lenses to be sent back for retooling when the lenses are tested at the factory. This, in turn, results in a higher price tag of the finished product. However, accidents still may happen during production and shipment, and it is not impossible for occasional duds to be delivered to unsuspecting buyers. Any camera older than an OM‑1 may not provide as good a match for this lens in critical capabilities like IS, AF and subject recognition. Even the OM‑1 (and its OM‑1 II junior brother, which uses the very same sensor) may be hard‑pressed when using only phase AF (in C‑AF mode) with this lens. Phase AF works by detecting light rays that converge onto the same point of the sensor from different directions. This is easier (i.e., the angle difference is wider) with a fast f/2.8 lens. An f/4 lens still works well on the OM‑1. An f/6.3 lens is likely not too far from the limit where the OM‑1 phase AF gives up, and is automatically replaced by contrast AF. Adding a TC brings phase AF further closer, or past, this limit. Quite a bit of nonsense is repeated on BBs (especially in the comments section at the end of reviews) every time a new Micro 4/3 lens is compared with lenses for other formats, and the OM System 150‑600 is no exception. On this page, I will only state a few facts: Online tests and reviewsWhen evaluating this lens for possible purchase, I downloaded test images shot by a few different reviewers. In particular, I found side‑by‑side tests of the 150‑600 and 150‑400 TC Pro. The results with the two lenses are closely comparable, although not identical. The difference is not so much in mere image resolution, but rather in a better and more natural‑looking color and contrast with the latter lens. Assuming that these results are typical of the 150‑600, and considering the large difference in price of these two lenses, I do acknowledge that the 150‑400 TC Pro is better, albeit priced way out of my reach. Even removing the price difference from the equation, the 150‑400 TC Pro is much bigger (i.e. requires a bigger backpack). On the other hand, the image quality of the 150‑600 is quite good enough for me not to have significant objections to using this lens. There are plenty of tests of the 150‑600 available online, some of them containing downloadable full‑size images shot with this lens. If you are considering a purchase of this lens, by all means check at least a few of these reviews, and download the original test images for a careful examination on your computer. AlternativesOlympus 100‑400 f/5‑6.3The Olympus 100‑400 non‑Pro is significantly more limited in maximum focal length than the 150‑600. Most of the time, I find myself shooting at 400 to 600 mm FL, so the 100‑400 is not a viable alternative for me. With the MC‑14 TC, focal length of the 100‑400 almost reaches 600 mm (560 mm, to be precise), albeit at almost f/8 fully open and slightly, albeit visibly, less sharp than without TC. In comparison, the 150‑600 is roughly one stop brighter without TC at 600 mm. The 100‑400 with MC‑20 is f/13 fully open at effective 800 mm FL, which is beyond the threshold of visible diffraction blur. Therefore, I do not recommend the TC‑20 for use with this lens. If 400 mm is enough for your uses, the 100‑400 can be a good alternative (see e.g. Robin Wong, Martin Belan). It also costs and weighs much less than the 150‑600. It can be equipped with the MC‑14 if, occasionally, you need to exceed its maximum FL. If you routinely need to exceed 400 mm, this is an alternative I do not recommend. Olympus 300 mm f/4 Pro

The 300 mm f/4 Pro is extraordinarily sharp (Figure 29), does not need to be stopped down to get sharper, and still performs well with both MC‑14 and MC‑20 teleconverters. It is also largely immune to flare and internal reflections (Figure 30). With backlit subjects, the worst that can happen is a slight loss of contrast. As a whole, this alternative provides at least as good an image quality as afforded by the 150‑600. There aren't many things to criticize about the 300 mm f/4 Pro. If one must, perhaps I can say that this lens displays a creamy bokeh in out‑of‑focus foreground, and a more "nervous" (also described as "harsh", "frenetic" and comparable terms) bokeh in the out‑of‑focus background (i.e. highlights turn into "bubbles" with a sharp brighter outline). The opposite would be desirable, since in wildlife photography there is virtually always a large out‑of‑focus background, but much less often a substantial amount of out‑of‑focus foreground. A "nervous" background bokeh is usually a sign of ovecorrected spherical aberration, which in turn may result from an optical design optimized for a reduced physical length of the lens. The problem with this alternative is the inconvenience of swapping a teleconverter in and out in the field, while precariously juggling the camera, lens and teleconverter. By the time I am again ready to shoot, there is a good chance that the subject has fled, or has settled into an uninteresting pose. Compared to the 300 mm + TCs, the 150‑600 adds a range of focal lengths below 300 mm, besides reaching the same maximum FL without needing TCs. I don't shoot wildlife very often below 400 mm FL, but it is nice to know that, with the 150‑600, I can count on this lower FL range if necessary, without needing to swap lenses.

A side‑by‑side comparison of the 300 mm and 150‑600 (Figure 31) shows in no uncertain terms why the latter weighs almost twice as much. Together with the 300 mm prime, I often carry also the 40‑150 mm f/4 Pro (roughly 400 g with caps and lens shade), to have access to a lower FL. The weight and size of the combined 300 mm f/4, 40‑150 mm f/4 and the two teleconverters approaches those of the 150‑600. Therefore, the higher weight and size of the 150‑600 versus the 300 mm is not really an argument in favor of the 300 mm, if you consider the additional equipment required to get around the FL limitation of a prime lens. The large number of optical elements in the 150‑600 (25, versus 17 in the 300 mm) makes this lens more sensitive than the 300 mm to flare, if shooting against the sun. The 4x zoom range of the 150‑600 also means that the lens shade of this lens, being designed to prevent vignetting at 150 mm FL, is too short and too wide to completely protect against flare at higher FLs. Both factors are intrinsic characteristics of zoom versus prime lenses, rather than specific to the 150‑600. OM System 150‑400 mm f/4.5 TC ProThe 150‑400 TC Pro is a faster lens than the 150-600, does not need to be stopped down, and is moderately better in overall image quality, but is priced out of the reach of most amateur photographers, including myself. The much larger size of the 150‑400, compared with the 150-600 collapsed to 150 mm FL, requires a substantially larger backpack. The weight of the 150‑400 TC Pro is 1.88 Kg without lens shade and caps, so it is actually lighter than the 150‑600, in spite of the larger diameter (115.8 mm vs. 109.4 mm), length (314.3 mm vs. 264 mm) and more complex optical scheme (28 elements in 18 groups vs. 25 elements in 15 groups). I can note the following in the 150‑400 TC Pro:

With the built‑in 1.25x TC, the 150‑400 TC Pro reaches a 500 mm FL. In addition, it can also use either the MC‑14 or MC‑20 (up to 1,000 mm FL with the latter and the built‑in TC, albeit at f/10 fully open). A 150‑600 with internal zooming and a constant physical length would require a different optical design than the present 150‑600, and a higher physical length than the 150‑400 TC Pro. A drawback of the 150‑400 TC Pro is that quite a few photographers might hesitate at the thought of taking a 10,000 € kit of lens and camera to remote field locations or on long‑haul flights. In late August, 2024, the lowest price of the 150-400 TC Pro on Amazon.de was 7,499 € (and the ready-to-ship stock at this price was just one lens). For what is worth, the bokeh of the 150‑400 TC Pro has been criticized, e.g. here. It looks much like the bokeh of the 300 mm Pro, discussed above, and of the 150‑600, which displays comparable characteristics (albeit gets significantly better when the lens is stopped down, see above). It has also been mentioned that post‑processing tools like Adobe Lightroom (version 13 and later) can process the background of images in order to smoothen the bokeh. OM System apparently assembles a 150‑400 TC Pro only after an order comes in, so this is not a lens you can buy on a whim and expect to receive after a couple of days. There are probably very small, or no, stocks of this lens ready to ship (Amazon EU seems to keep a stock of one or two specimens, for example, but if you order yours at the wrong time, you may need to wait for Amazon to order, and receive, a replacement from OM System). Some early specimens of the 150‑400 TC Pro were made in Japan, while later ones were made in Vietnam (there are reports of faulty specimens among the latter). My conclusionFor my needs, I can see no real alternatives to the 150‑600 mm among the current Micro 4/3 lenses. If you already own the 300 mm f/4 ProAnother question is whether it is worth buying the 150‑600 if, like me, you already own the 300 mm f/4 Pro, MC‑14 and MC‑20. This is a harder question to answer. Although there is a considerable overlap in focal lengths between the two alternatives, the brighter 300 mm and its better native image quality have an edge at lower illumination levels, while the 150‑600, being a zoom, is much more effective whenever the required focal length may suddenly change (which means almost always, for wildlife in the field). In other words, the choice is between being able to do more cropping in post‑production with the 300 mm + TCs, versus zooming in the field with the 150‑600 to take full advantage of the FL range of this lens. How about selling your 300 mm and buying the 150‑600, instead of keeping both? The 300 mm is significantly lighter, faster (f/4 vs. f/5.8 for the 150‑600 at 300 mm FL), and optically better fully open than the 150‑600 at 300 mm. It also has a better weather sealing, and probably a better AF. Eventually, I would end up missing the 300 mm. Consequently, for now I decided to postpone any decision to sell the 300 mm. Only a careful weighting of the advantages and costs of the alternatives can give an answer in your specific case. PriceUntil late June, 2024, the OM System 150‑600 remained priced at 2,699 € on Amazon DE (Germany), and a little higher on Amazon SE (Sweden). These were the prices for direct sales from Amazon, and roughly the same as the current price for the 300 mm f/4 Pro. At that time, retailer prices for the 150‑600 were higher still. In early July 2024, the Amazon DE price suddenly dropped to 2,375 €. A further discount during checkout brought the Amazon DE price down to 2,281 € including shipment to Sweden, and I pulled the trigger. Within three weeks afterward, the price at Amazon DE had risen back to 2,499 € and the checkout discount had disappeared. By late August, the lowest price was 2,638 € (sold by an Amazon.de seller, and at the time not available directly from Amazon.de).

The price on Amazon SE remained essentially unchanged during the same period, except for a very minor, temporary discount of less than 20 €. Then it suddenly rose to nearly 3,000 € in September (Figure 32), the highest price for this lens I have seen. I understand how the price in one EU country (Germany) can temporarily decrease by a good amount, because of discount campaigns. I fail to understand, however, the commercial logic of the price first failing to decrease by a comparable amount in another EU country (Sweden), and then increasing by an unreasonable amount in the latter country. Do they think that Swedish customers will not check the prices in nearby EU countries? Regardless of which national EU site one uses to place an order, the lens will very likely ship from the very same Amazon packaging center in Germany, so there is no tenable reason for such different prices. As you can see, it does pay off to check multiple Amazon EU national sites before you pull the trigger. You only need to register as an Amazon customer on a single Amazon site. The same account is automatically recognized by all other Amazon sites. You do need to enter the web address of the desired national Amazon site in your browser. If you are not in a hurry and can wait 2‑3 months for the lowest price, you may benefit from one of the temporary cashback campaigns that OM System uses to announce on short notice several times a year, especially in proximity of major holidays and before the summer and winter vacation seasons. Resellers advertising on Amazon often participate in these cashback campaigns, which means you pay the full price first, then apply separately for the cashback on the OM System web site and submit a copy of the invoice, and finally receive the money after a few weeks. It appears that Amazon, as a direct seller, does not participate in these cashback campaigns, and instead offers the corresponding discount up‑front with no need for the buyer to apply for refund of the discount after the purchase. Aside from temporary discounts, Amazon as a direct seller, as a rule, charges a lower price than resellers advertising on Amazon. Amazon additionally may offer free shipment (usually within the same country, e.g. free shipment within Germany from Amazon DE). The Sigma 150‑600 Sports can be found, on Amazon DE, for around 1,850 €. Therefore, at the time I bought it the markup of the OM System lens over the Sigma lens had reduced to around 430 €, but subsequently returned to over 800 €. The Sigma lens was significantly more expensive than at present when released. How much of the markup applied to the OM System lens is justified, with respect to the Sigma lens? OM System has three types of expenses in the production of this lens. The development cost is a one‑time, up‑front expense. This justifies a higher markup at the release of the product to recoup a significant part of the development cost, but the lens price must decrease afterwards, so that sales can pick up. The customized components of the 150‑600 (mainly electronics and electromechanics) are probably a little more expensive than the original Sigma components (by a few tens of €, not hundreds). This part of the production cost remains constant. As for the percentage of OM System‑branded lens specimens that must be sent back for retooling because they do not pass the Micro 4/3 tests during and after production, we do not know whether this percentage is similar to that of Sigma‑branded lenses, or higher. In the latter case, this is an additional, permanent cost for OM System. On top of these costs, both OM System and Sigma must apply a reasonable margin of profit. I believe the 150‑600 is still a little overpriced at the price I paid, especially considering that most buyers are now aware that this OM System lens is not a new design, but optically and mechanically identical to a three years old Sigma lens. There is perhaps room for a drop in ordinary price to 2,100‑2,200 € over the next couple of years.

On October 3, 2024, 43rumors.com announced a 700 US$ reduction in the price of the 150-600 at several of the largest US retailers, including amazon.com (Figure 33). A few days later, prices in the EU were still unchanged. This means that the amazon.se price is now (2024-10-06) almost 1,000 US$ higher (i.e. 50% higher) than at amazon.com. Over the years, several of the models of Olympus/OM System lenses I currently own have slowly increased in price, rather than decreased (e.g. the 300 mm f/4 Pro has increased by a good 30% since I bought it in 2016). Olympus/OM System lenses are far from unique in this respect. For example, the CoastalOpt (now Jenoptik) 60 mm f/4 Apo increased by over 80% since I purchased it in 2013. The last time I actually saw a price quote for this lens was in 2021, and if anything the price has further increased since that time. The OM System 150‑600 is probably too new for second‑hand specimens to be available at realistic prices in the EU or USA. It may already be possible to find second‑hand specimens in Japan, instead, where photographers seem much more willing to purchase new equipment and sell it after a short time at a significantly lower price. ConclusionsThe OM System 150‑600 mm f/5‑6.3 is based on the Sigma 150‑600 mm f/5‑6.3 Sports, with cosmetic, electronic and electromechanic customizations, but no customization of the optics except for light baffles and probably for a testing procedure optimized for Micro 4/3 sensors. It is a good‑quality zoom, optically slightly less good than the Olympus 300 mm f/4 Pro and the OM System 150‑400 TC Pro. Without a teleconverter, the image quality can be described as very good in the 150-400 mm FL range, and very good if stopped down in the 400-600 mm FL range. The 150‑600 is by far faster and more versatile to use in the field, compared to using the 300 mm f/4 Pro and teleconverters. The optimal way of using the two lenses differs. The 300 mm prime with teleconverters is more tolerant of extensive cropping in post‑production. The 150‑600 should be zoomed in the field to the desired subject framing, because cropping in post‑production does display the lesser image resolution of this lens. The 400‑600 mm range of focal lengths is the one I most often use. Therefore, there are no real alternatives to this lens among current Olympus/OM System or third‑party Micro 4/3 lenses. The weight of the 150‑600 is 2.21 Kg including the lens shade, almost twice the weight of the 300 mm f/4 Pro. Adding to a 300 f/4 Pro a kit of 40‑150 f/4 Pro, MC‑14 and MC‑20 makes the total weight approach the 150‑600. The kitted‑up 300 mm is also far more expensive than the 150‑600. The 150-600 is not so sharp fully open in the 500-600 mm FL range. It needs to be stopped down to f/8 to f/9.5 for maximum sharpness in this range. The 150‑600 is not marketed as a Pro lens. Its weather sealing is IPX1 certified, which is lower than some cameras and Pro lenses. The price markup of the OM System 150‑600, compared to the Sigma 150‑600 Sports, is only partly justified. Although prices temporarily dropped by 418 € on Amazon DE in July 2024, this lens was still overpriced by perhaps 150‑200 €. |